One of the most heartwarming things to read about while I prepare posts for this blog is when I read about individuals and organizations that do amazing things (nothing short of mission impossible stuff, if you ask me), to preserve humanity. I come across such information after I choose an artifact to introduce, such as with my post about the Lyre of Ur, and it is quite wonderful.

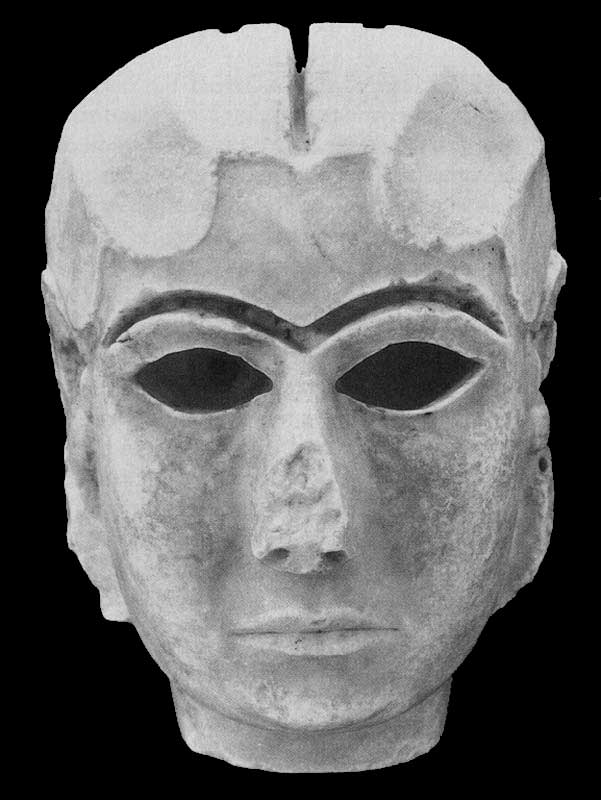

Today, I would like to talk about an artifact as mesmerizing and beautiful as the Lyre of Ur, which was also tragically looted in April 2003. The Mask of Warka, or the Lady of Uruk, or the Sumerian Mona Lisa, as this artifact has been called, is considered to be one of the very earliest representations of the human face in the history of humanity.

The mysterious Mask of Warka, aka The Sumerian Mona Lisa. (Source)

0

Possibly dating to as far back as 3300 BC and as late as 3000 BC, the 5,000-year-old mask is made of marble and was found in the temple precinct of Innana, Uruk, a city-state of Sumeria, where writing got its start around 3200 BC.

This is humanity galore, people.

According to Dr. Bahnam Abu Al-Soof’s website, http://www.abualsoof.com, the Mask of Warka was originally attached to a larger statue made of various materials. The mask was excavated in modern-day Warka in Iraq by German archaeologists who began their excavations in 1912. Uruk-Warka, is one of the earliest cities, once ruled by the legendary King Gilgamesh, and mentioned in the Genesis as the biblical city of Erech.

Ruins at Uruk-Warka, where the Sumerian Mona Lisa was unearthed. (Source)

You can see more great pictures of Uruk-Warka from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago here.

The Mask of Warka went missing in April 2003, and became one of thousands of irreplaceable pieces of humanity that were taken from the Iraq Museum.

Enter Marine Reserve Col. Mathew Bogdanos, and an individual who cares about humanity is in the picture. Bogdanos, who has a passion for classical history and holds a master’s in classical studies, headed an investigation to help find looted artifacts in and around Baghdad in 2003. Thanks to his implementation of a systematic investigative approach he might use even in an investigation in Manhattan, where he is an assistant district attorney, artifacts were recovered, including the Mask of Warka.

Very little is known about this mask, and I have to admit that I had some trouble finding much of anything about it beyond its bare description and the fact that it had been found after being looted. The bulk of the information available about the Mask of Warka is just the announcement that it was found in September 2003, just five months after its disappearance, buried in a farmer’s garden.

Bogdanos said in a PBS interview, which you can watch or read here, that as part of the effort to recover missing artifacts, he adopted a system of circulating wanted posters with pictures of the artifacts on them. Thanks to that approach, the recovery of the mask consisted of an Iraqi coming forward and pointing Bogdanos’s team to a farm where such items were hidden. Bodanos’s team found out from the farmer that the artifact had changed hands several times before it ended up on his farm, after its disappearance generated enough attention to make it difficult to take out of Baghdad.

Colonel Bogdanos was slated to return to civilian life in October 2003, so all of this is old news, I suppose, but what this man, and so many people have done to make right what so many did wrong in April 2003, is something we should never forget.

Sources:

http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/sites/Uruk/Uruk_1.htm

http://ancientneareast.tripod.com/Uruk_Warka_Erech.html