Because this is a dog year in the Chinese zodiac, and because dogs are now helping sniff out looted artifacts from Iraq and Syria, plus I love dogs, it seems a good time to talk about how Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians–Mesopotamians–were all major dog people.

The first dog people.

Sit, Ur-Gi, Sit

- Babylonian man who’s clearly a dog person, and his dog. (Source)

It is commonly believed (and seemingly supported by tangible evidence to an amateur) that soon after the dog (ur-gi in Sumerian) was first domesticated, the dog collar was developed in Egypt. But, as with a lot of things, it is actually ancient Sumer where that took place.

Archaeological evidence from Egypt dates further back than that from Mesopotamia, but in an article at Ancient History, titled, “Dogs in Ancient Egypt,” Joshua J. Mark still writes that dog collars and leashes were of Sumerian origin:

“The dog collar and leash were most likely developed by the Sumerians earlier although evidence for both of these in Mesopotamia appears later than 3500 BCE in objects like a golden Saluki pendant from Ur dated to 3300 BCE.” (Source)

Further, in another Ancient History article, titled, “Dogs & Their Collars in Ancient Mesopotamia,” Mark reiterates the belief that Mesopotamia was where domesticated dogs in collars first appeared, even, curiously, after declaring the difficulty of saying so with certainty:

“In the same way that scholars debate the origin of the dog and its first domestication, it is difficult to say with certainty that the people of Mesopotamia were the first to invent the collar. It is probable, even quite likely, that the collar – like people’s relationship with dogs themselves – developed independently in many different regions at different times. Even so, as far as the collar’s depiction in ancient art is concerned, the earliest come from Mesopotamia.” (Source)

Well, who am I to argue? Regardless of where dogs first began donning collars and getting led on leashes, Mesopotamians domesticated dogs for practical purposes like everyone else; security for their dwellings and their herds, as well as hunting.

But as we will find out, that package came with a lot more perks, and as we know…it was pretty freakin’ great.

- This plaque found at the palace at Nineveh depicts Assyrian hunters with their hounds. (Source)

But let’s start at the beginning of this relationship.

To enter an ancient Mesopotamian city or village was to see collared dogs roaming freely, cleaning up carrion messes while guarding those human dwellings, along with the assets essential to their survival within them. They wore collars, because though they spent their days roaming free, they each had a master who cared for them and considered them the family pet.

Such an arrangement created the perfect environment in which the relationship between humans and dogs went beyond that of practicality and became one of companionship and love, the relationship all dog people have with their pooches today.

Good Dogs

- Statue of a very good Mesopotamian dog, c. 5000-1000 BCE. (Source)

Though surely there were mutts, there were three main breeds of dog we know existed in ancient Mesopotamia; the Greyhound (which includes the Saluki type), the Dane, and the Mastiff. Mark quotes historian Wolfram Von Soden, whom I attribute the last statement to, describing the types of dogs and for what practical purposes they were each best suited:

“As far as we can tell, there were only two main breeds of dog: large greyhounds which were used primarily in hunting, and very strong dogs (on the order of Danes and mastiffs), which in the ancient Orient were more than a match for the generally smaller wolves and, for that reason, were especially suitable as herd dogs.” (Source)

Further descriptions of the types of dogs found in Mesopotamia come from inscriptions such as one from the Ur III Period (2047 – 1750 BCE), describing large mastiff-like creatures coming into the city with their handlers, wearing thick collars and leashes that one can only guess were made of leather.

For a clearer picture of what the dogs of Mesopotamia looked like, here is this simple video.

They Liked Them & Put Collars on Them

- Plaque from Sippar depicting a man leading a large dog on a leash, possibly a Mastiff, dating to the Old Babylonian Period (2000 – 1600 BCE). Note the wide collar, rope tied twice around the dog’s neck. (Source)

Pretty much all depictions of dogs from Mesopotamia showed them wearing collars, all of which were wide to protect the animal’s neck. The earliest version of the collar was probably just rope that was wound around the dog’s neck multiple times (as in the image above) or a piece of sturdy cloth, which then probably evolved to the leather version I mentioned earlier.

According to Mark, though people from all rungs of the social ladder owned dogs in ancient Mesopotamia, dogs belonging to masters of the upper class wore collars that not only bore their names, but also their masters’.

The significance of the collar goes beyond its practicality, then. Mark, in the “Dogs & Their Collars in Ancient Mesopotamia” article, writes that the dog collar also served as a sort of testament to people’s inclination to spoil their pooches whom they felt were worthy of such an accessory.

Mesopotamian Belly Rubs

When looking at all there is to look at, whether art or any kind of literature featuring dogs from ancient Mesopotamia–and especially knowing their collars sometimes bore their names–it’s easy to see that the status of our best friend was high in more ways than one.

Today we have our pooches’ pictures on our phone lock screens, and that’s just scratching the surface of how we worship them. Well, Mesopotamians worshiped their dogs, too. Sometimes literally. Sometimes by having their image on the equivalent of the Mesopotamian phone lock screen – cylinder seals. Cylinder seals were used to identify individuals in writing, like a signature. Dogs making it into a person’s signature further drives home the importance of the intimate relationship people had with their dogs.

- This cylinder seal dating back to the 2nd millenium BCE, features a male worshiper with a dog. Note the collar on the dog. (Source)

Best Friends with Benefits

Dogs were first and foremost domesticated for practical purposes, but alongside the universal ones, Mesopotamians got a few extra magical ones. They equaled, and were synonymous with, protection, not just in the practical ways in which we still rely on them, but also in the spiritual and supernatural sense; they protected humans against angry gods, ghosts, evil spirits, and demons.

- The golden pendant of the saluki from Uruk, c. 3300 BCE, housed at the Louvre in Paris. (Source)

The labyrinthine pantheon Mesopotamians worshiped, and their belief that every deed done or not done counted and every action had a reaction, made them take very practical and serious measures to protect themselves from any vengeful gods, or worse, demons.

Along with incantations and prayers, physical objects were produced as a line of defense. The golden dog pendant pictured above is a protective amulet that was worn or carried by its owner. In the ruins of Nineveh, dog statuettes with inscriptions saying they are for protection were found buried beneath an entrance to the North Palace. At the city of Kalhu (Nimrud), five dog figurines made of clay, known as The Nimrud Dogs, were also found with the same kind of inscriptions identifying them and their purpose.

-

Clay dog figurines found buried underneath a North Palace entryway at Nineveh. Inscriptions on their bodies include declarations such as: “Loud is his bark!” (Source)

It was during Hammurabi’s reign (c. 1792 – 1750 BCE) that the practice of creating clay or bronze figures of dogs took off in ancient Mesopotamia, not to be cute and have the likenesses of pets to decorate with, but for security. Such sacred knickknacks were buried in multiples beneath entrances to buildings, including those of palaces, as mentioned above. Rituals preceded these burials, during which incantations were recited to awaken the protective spirit of the dog in the object being buried.

Dogs and Gods

-

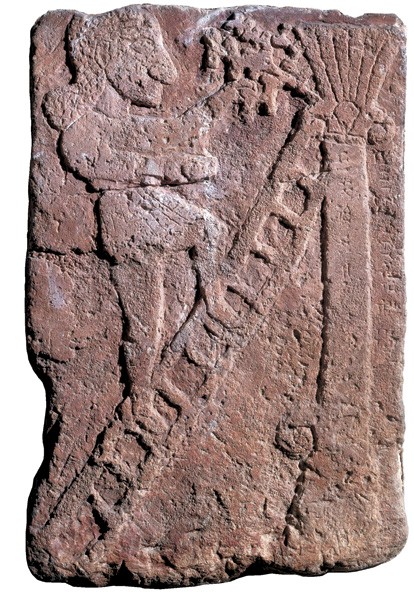

A plaque dating back to the reign of Babylonian king Nabu-mukin-apli, 978-943 BCE, showing Gula with one of her pooches. (Source)

In her book, The Healing Goddess Gula: Towards an Understanding of Ancient Babylonian Medicine, Barbara Böck writes about Lamashtu, a demon whose “specialty is killing babies,” among other horrible things. To protect their babies from Lamashtu, Mesopotamians called on Gula and her dogs.

Gula, among other things, was the goddess of healing and dogs. She is always either depicted with a dog at her side (as shown above) or as a dog herself; it was during the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000- 1600 BCE) that her symbol became simply the dog.

When Gula was called upon through an incantation to keep Lamashtu from snatching a baby, her dogs faced the demon and threatened her:

“We are not just any dog, we are dogs of Gula, poised to flay your face, tear your back to pieces, and lacerate your ankles.” (Source)

You’ll note that Gula is primarily the goddess of healing, though she wears a few more hats, including that of being the goddess of dogs, but what do those things have to do with each other so that they exist in one deity?

Well, dogs were the sacred companions of Gula because they were healers themselves. The saliva of dogs, which Mesopotamians observed could heal wounds, was valued as medicine.

Another part of Gula that the Mesopotamian view of dogs drew from is the fact that the goddess was also associated with the underworld and transformation, things people experience after death. Dogs in this context were the companions of the dead on their journey to the afterlife, where they might have to face demons or other unsavory characters they need protecting from.

It’s a very bittersweet thing, the heights the relationship between dogs and humans reached, especially when you take into consideration that it was children whom dogs accompanied the most on their journeys to the afterlife. (No, I’m not crying, you are.)

Going back to the part about her being the goddess of dogs, Gula protected them (along with cats…this goddess is my kind of goddess), and as Böck writes, a partially-preserved prayer to Gula makes it clear that not doing right by a dog, alive or dead, is really not okay with her:

“He has shown great disrespect which before Gula…

[He saw…] but pretended not to notice it. He saw a wounded dog but he pretended [not to notice it].

He saw [a…dog] but pretended not to notice it. The dogs [were] fighting…

[…they were wai]ling and he saw it but pretended not to notice it…

[He saw a dead dog] but did not bury it and threw it to the ground…

…the dogs were fighting but he did not remove them…” (Source)

Keep in mind, we’re talking about a deity associated with the underworld, which means it’s best to not anger her, or you might need to find another way to protect yourself from harm. And you might as well forget about a dog coming to your rescue then.

Long Before Lassie

Domesticated dogs in collars and on leashes also made plenty of appearances in Mesopotamian literature. Samuel Noah Kramer, author of History Begins at Sumer, wrote that dogs are referred to in 83 proverbs and fables.

In The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Descent of Inanna, we see that Gula was not the only deity accompanied by dogs. In the former, the goddess Inanna (Ishtar) makes her appearance accompanied by seven hunting dogs wearing collars and being led on leashes. In the latter, the god Dumuzi (Tammuz) keeps a royal retinue that includes domesticated dogs in the underworld where he resides.

These dogs are the protectors and companions of these deities, and especially in the case of Inanna, who was often called upon for protection. The dogs were that extra level of divine protection.

As Kramer notes, according to Mark, along with such elevated roles in mythology, dogs were also the subject of fables that showcased loyalty, unconditional love, and the protective nature of our best friends to impart wisdom, as fables do. In fact, some of Aesop’s fables were not his at all, but rather Sumerian ones written centuries before Aesop (c. 620 – 564 BCE) was even alive, but that’s another topic for another time. Two such fables were, Why the Dog is Subservient to Man and The Show Dog, which are summarized quite well here, but essentially highlight the attributes of dogs, such as loyalty, unconditional love, and fierce protectiveness.

The interesting aside I want to point to is that Mesopotamians had dog shows, and this is something that, according to Kramer, helps support the idea that domestication and the collar in Mesopotamia predated those things in Egypt.

All Dogs Go To Heaven

- Dog paw prints accidentally and wonderfully left in clay, from Ur, c. 2047-2030 BCE. (Source)

At Gula’s most prominent temple at Isin, where dogs considered sacred roamed and were taken care of by the priests and priestesses there, underneath the ramp leading up to the building, 30 actual dogs were found buried.

Böck writes that although the dogs might have been sacrificial, it is also possible they were just the sacred dogs of the temple whose burial was simply a way to honor them after their natural passing, as Gula liked.

Of course, I choose to believe the latter option.

I choose to believe the latter option, because I can’t imagine that even in the harsh world of antiquity, where live animals were often buried with their owners in order to accompany them to the afterlife, anyone could stomach a stand-alone sacrifice of a protector, healer, and best friend. I choose to believe that the dog has always, from day one, held a large chunk of humanity’s collective heart. I choose to believe we’re all dog people if we all knew what our ancestors figured out about the creature that is love itself.

Sources and further reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saluki

https://www.ancient.eu/article/1031/dogs-in-ancient-egypt/

https://www.ancient.eu/article/1175/dogs–their-collars-in-ancient-mesopotamia/

https://archive.org/details/Kramer1956HistoryBeginsAtSumer

https://www.ancient.eu/article/215/inannas-descent-a-sumerian-tale-of-injustice/

https://www.ancient.eu/Inanna/

http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/gods/lords/lordumuzi.html

https://www.ancient.eu/article/1001/the-nimrud-dogs/

https://www.ancient.eu/article/846/cylinder-seals-in-ancient-mesopotamia—their-hist/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isin

http://www.ancientneareast.net/mesopotamian-religion/lamastu-lamashtu/