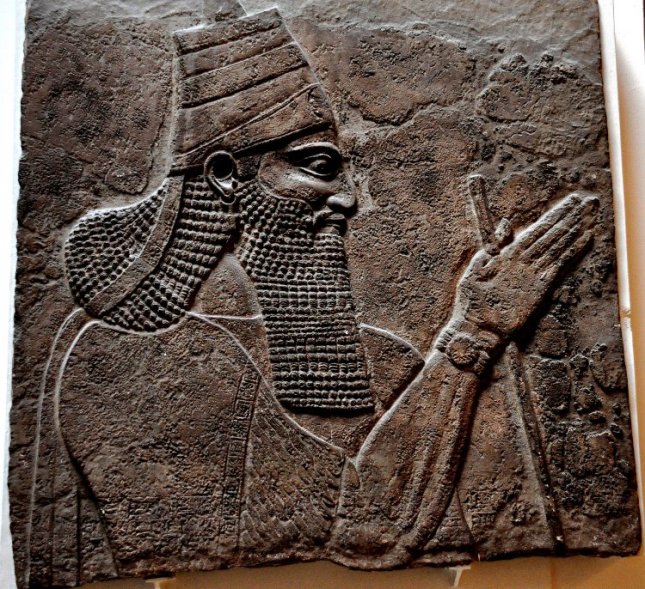

Look at this bas-relief found at a palace in Nimrud…

…it depicts the humiliation of one man by another.

Some sources identify the prostrate figure as Hanunu, a king who ruled Gaza in the 8th Century BCE. Others simply identify him as a captured enemy.

Either way, the one thing everyone agrees on is that the foot placed upon his neck belongs to Tiglath-Pileser III (745 – 727 BCE), an Assyrian king who laid the groundwork for modern imperialism and began a long line of Assyria’s greatest kings.

Whooooooo Was He/Who-Who Who-Who?

Tiglath-Pileser III is the first king we’re covering at All Mesopotamia that has been mentioned on the Assyrian King List (as well as the first Assyrian king to be mentioned in the bible). Though his reign is nowhere near being the first to occur within the traditional (and disputed) timeline of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (934 – 610 BCE or 912 – 612 BCE), some scholars believe this era began with Tiglath-Pileser III’s ascent to the throne in 745 BCE.

Being the third ruler in Assyria to carry the name Tiglath-Pileser—which is the Hebraic form of the Akkadian Tukulti-apil-Ešarra, which translates to “my trust/support is in the son of Esharra,” which refers to Ninurta, the god of war and hunting—you’d think he was related to at least one of the other two Tiglath-Pilesers. But he wasn’t. The first and second Tiglath-Pilesers ruled during what scholars have labeled the Middle-Assyrian period; one was during the 11th Century BCE, the other in the 10th Century BCE, respectively.

The gap grows wider and the direct relation is completely taken off the table when we remember that the third Tiglath-Pileser’s reign was in the 8th Century BCE.

Nonetheless, there is blood in this story.

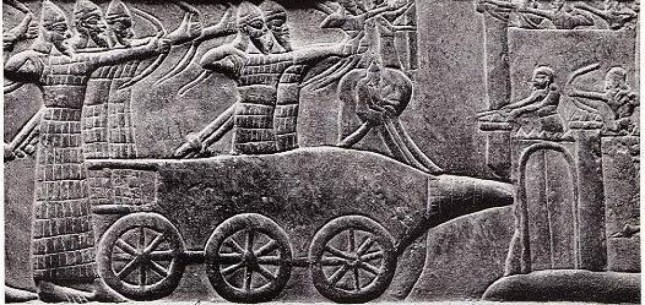

Tiglath Pileser III shown in his chariot in this panel from his palace at Nimrud. (Source)

Of course, it’s not uncommon for unrelated kings to share a name, especially when the name is a nod to a deity (and truth be told, Tiglath-Pileser III never linked himself to his first two namesakes), but what makes TPIII’s choice so interesting is the inherent murkiness of his origins. (I will call him TPIII throughout the rest of this post.)

Though he presented himself as the son of Adad-nirari III (811 – 783 BCE), scholars question the truth of this relation, because there are three other guys between Adad-nirari III and TPIII on the Assyrian King List. Also, two of those guys are the actual sons of Adad-nirari III, with his grandson ruling in the gap between their reigns.

Oh, and another thing: in 1892, a stele was discovered that showed TPIII’s name imprinted over one of those three guys’ names. Add to that the scantiness of information about anyone mentioned here, including Adad-nirari III, and you’ve got yourself a fishy situation in some very murky (and bloody) waters.

The Assyrian Shady

So, how did such a shady character become one of the most powerful kings of Assyria?

Let’s start with the name Pulu.

Pulu (or Pul as he appears in the bible) was the governor of Kalhu (Nimrud), the capital of a stagnant and waning Assyrian empire, one that was dealing with regional rulers with too much power, serving (or not) under ineffectual kings who were hardly maintaining what their long-gone predecessors had built.

Meanwhile, Assyria’s army, known the ancient world over as the greatest, also began to lose its luster when in 754 BCE it met its match in the kingdom of Urartu‘s army…and lost.

This loss was a significant disaster for Assyria; it grew an already-existing fissure in the empire as its vassal states and allies began to undermine Assyria and look to Urartu as an alternative power to whom they would pledge allegiance. This shift in loyalties also affected Assyria’s coffers, which had been regularly filled with tributes from those very vassal states and allies now looking for other ways to “invest,” if you will. The ripple effect of this loss was long-lasting and reached as far as Babylonia in the south, where in 749 BCE forces were dispatched to protect Assyrian interests.

Needless to say, things just weren’t going well for Assyria during this time, and poor Ashur-nirari V (754 – 745 BCE) had not been king for long before he had to bear the brunt of a half century’s worth of failure and unrest. All this led to civil war, which broke out in 746 BCE and saw the royal family slaughtered, giving way to Tiglath-Pileser III, new king and former governor of Kalhu, aka Pulu.

Really, Machiavelli would’ve given Pulu a nod of approval for slaughtering his way to the top, and, more importantly, setting things up so that the same thing wouldn’t happen to him. Because as we will see, Pulu had a lot of work to do, and he wanted (and apparently needed) it done right.

First Things First

Since it takes one to know one, TPIII’s first order as king was to take power back from regional rulers.

He started by cutting up the larger, more rebellious provinces into little pieces. Over a period of seven years, TPIII had fashioned some 80 provinces through this technique. He then appointed eunuchs to govern all those provinces.

“Two court officials – who are beardless and, therefore, possibly identifiable as eunuchs – are shown marching toward the king. The second figure motions to the line of men that stood behind him to come forward toward the king.” (Source)

Of course, appointing eunuchs would get another Machiavellian nod, as according to Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (and basic biology), eunuchs were a great way to maintain control over who occupies a position of power without the complication of heirs, much less a pedigree that mattered.

More, More, More

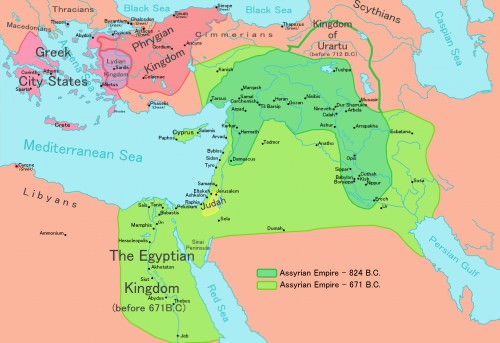

As I said before, TPIII is credited by some scholars with the founding of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which some historians believe is the world’s first true empire (sorry, Sargon of Akkad). It was a period during which Assyria grew to an area stretching from Asia Minor to Egypt by 671 BCE. This, despite being a geographically vulnerable nation.

The expansion and expanse of the Assyrian Empire–they even had Cyprus! (Source)

It was really a “domino effect” that turned a nation with vulnerable geography into the world’s first superpower, one always on the offense rather than the defense. This effect is described well by Dattatreya Mandal in a Realm of History article titled, “10 Fascinating Things You Should Know About The Ancient Assyrian State And Its Army“:

“Simply put, this terrain rich in its plump grain-lands was open to plunder from most sides, with potential risks being posed by the nomadic tribes, hill folks and even proximate competing powers. This in turn affected a reactionary measure in the Assyrian society – that led to development of an effective and well organized military system that could cope with the constant state of aggression, conflicts and raids (much like the Romans).” (Source)

TPIII took over an army that had already perfected siege warfare and had genius battlefield tactics, and even featured the world’s first separate engineer corps. This History On the Net article titled “Assyrian Empire: The Most Powerful Empire in the World,” details that perfection:

“The Assyrians were the first army to contain a separate engineer corps. Assyrians moved mobile ladders and ramps right up against heavily fortified city walls. Sappers and miners dug underneath the walls. Massive siege engines became prized Assyrian armaments.” (Source)

This was also an army that had been incorporating the psychology of fear into its strategy. In an Ancient History Encyclopedia entry, the historian Simon Anglim is quoted on this combination of Assyrian war methods and its effect on warfare as we know it:

“By these methods of siege and horror, technology and terror, the Assyrians became the unrivaled masters of the Near East for five centuries. By the time of their fall, their expertise in siege technology had spread throughout the region.” (Source)

Nonetheless, this great army had just met its match and lost.

Knowing he would just be another ineffectual leader of a doomed empire if he didn’t think outside the box, TPIII created what all scholars indisputably credit him with: the world’s first truly professional army.

You and What Ar–Never Mind

Unstoppable. Not to mention incredible. (Source)

We have to acknowledge that TPIII’s predecessors accomplished a lot with what all armies were at the time: essentially part-time and made up of mostly farmers during their off-seasons, and mercenaries. As the Assyrian empire grew, however, so did its internal problems and need for a full-time force to protect its interests from within as well as without.

Being that he had more than a few corrected provinces to work with now, TPIII introduced a system that required each one of those provinces to designate a certain number of men to be professionally trained, full-time soldiers. In a DailyHistory.org post titled, “How did ancient Professional Armies develop?”, Mark Altaweel details this part of a multi-pronged approach to vamping up the Assyrian army:

“These army units began to have distinct ranks and be part of specialized units within the military,” Altaweel writes. “This included the chariotry, cavalry, and infantry units; specialized units also included naval units consisting of Phoenicians. Other specialized soldiers include engineering units used for siege warfare.”

The overhaul extended further, all the way to command. “In addition, the army’s command structure became more sophisticated with developed ranks, similar to modern militaries,” Altaweel writes.

TPIII also made sure to reserve high ranks for pure Assyrians rather than those absorbed through conquest; cavalry, heavy infantry, and charioteers were all native Assyrians.

This overhaul, particularly locking in individuals with nothing on their schedule but soldiering year-round, translated into a gargantuan advantage over any other army in the world at the time, all of whom, Altaweel points out, still had a shortage of men during planting and harvest seasons. I can only imagine that to be attacked by the professional Assyrian army often entailed an imminent familiarity with the element of surprise for the attacked.

In the image above, you see a small part of what a siege carried out by the Assyrian army looked like; the skill of professionally-trained men with advanced weaponry, alongside technology. It was only through that multi-faceted approach to war and siege that TPIII was able to avenge Assyria’s defeat to the kingdom of Urartu and move on to destroying its difficult ally, the city of Arpad.

Arpad‘s defeat was no easy feat–it took three years to bring that city down. This tidbit serves as a testament to the strength of Arpad, of course, but it also speaks to the otherworldly capabilities of TPIII’s relentless army.

In his “Assyrian Warfare” entry for Ancient History Encyclopedia, Joshua J. Mark puts into perspective what Arpad was up against during its three-year siege, and why its considerable strength was still not enough when facing TPIII’s new and improved army:

“Campaigns such as the long siege of Arpad could only have been carried out by a professional army such as the one Tiglath Pileser III had created and, as the historian [Peter] Dubovsky notes, this expansion of the Assyrian Empire could not have taken place without ‘the new organization of the army, improved logistics and weaponry’ and, in particular, the use of iron weapons instead of bronze.” (Source)

No other army had the resources the Assyrian war machine had: fast-made iron weapons and armor. Note, this could only happen by way of Assyria’s hegemony over iron ore-producing regions while everyone else’s weapons were still made of bronze. This is not including advanced engineering skills, unbeatable tactics and, of course, TPIII’s mind and ambition.

“Tiglath Pileser III’s brilliant successes in battle lay in his military strategies and his willingness to do whatever it required to succeed in his objectives,” Simon Anglim writes of TPIII’s recipe for success.

Everybody’s Gonna Protect Their Feet

Shoes really make or break an outfit, and the Assyrian army boot really tied the whole professional army thing together. (Source)

For an army to fight year round, it needs to be an all-weather and all-terrain one. This cannot happen without the proper footwear. Enter my favorite and the coolest of TPIII’s innovations and inventions: the army boot.

On the significance and features of the Assyrian army boot, Mark quotes the historian Paul Kriwaczek:

“…the Assyrian military invention that was arguably one of the most influential and long-lasting of all: the army boot. In this case the boots were knee-high leather footwear, thick-soled, hobnailed and with iron plates inserted to protect the shins, which made it possible for the first time to fight on any terrain however rough or wet, mountain or marsh, and in any season, winter or summer. This was the first all-weather, all-year army.” (Source)

Further, in his book, The Great Armies of Antiquity, Richard A. Gabriel describes the specific ways in which the “jackboot” was beneficial to its wearer:

“The high boot provided excellent ankle support for troops who fought regularly in rough terrain … The boot kept foot injuries to a minimum, especially in an army with large contingents of horses and other pack animals.” (Source)

There’s not much else left to say about this accomplishment by TPIII, except it was such a great one, it wasn’t long before it became an everlasting staple of every military on earth…not to mention my personal favorite style of boot.

The Walls Come Down

With an area stretching as far as the Mediterranean, there was a lot of land full of people for TPIII to work with to make his empire not only bigger, but better.

Along with slaughter and slavery, the norms of war in antiquity, it was common practice and standard procedure in Assyria to deport defeated subjects, particularly if they had abilities and skills beneficial to the empire. This is a policy that TPIII is often credited with instituting, but it was actually first instituted by Adad-Nirari I in the 14th Century BCE. Nonetheless, he did it on such a big scale, it became a part of his legacy.

Now, deportation did not have the same connotation it does today. Like I said, to be deported under Assyrian rule was really to be resettled by being sent to a province where the empire needed more settlers with practicable skills.

In the Ancient History Encyclopedia Tiglath Pileser III entry, Karen Radner describes such events:

“We must not imagine treks of destitute fugitives who were easy prey for famine and disease … the deportees were meant to travel as comfortably and safely as possible in order to reach their destination in good physical shape . . . the ultimate goal of the Assyrian resettlement policy was to create a homogeneous population with a shared culture and a common identity – that of ‘Assyrians’.” (Source)

To ensure deportations went smoothly and subjects arrived at their destinations in good physical shape, it took an organized effort that went well beyond just keeping these people moving toward their destination. Take this letter written by an official handling a deportation of Aramaeans ordered by TPIII:

As for the Aramaeans about whom the king my lord has written to me: ‘Prepare them for their journey!’ I shall give them their food supplies, clothes, a waterskin, a pair of shoes and oil. I do not have my donkeys yet, but once they are available, I will dispatch my convoy. (Source)

Even after the arrival of the deported subjects at their final destination, that official’s work of ensuring the welfare of his charges was still not done, as we see in another letter he wrote to TPIII:

As for the Aramaeans about whom the king my lord has said: ‘They are to have wives!’ We found numerous suitable women but their fathers refuse to give them in marriage, claiming: ‘We will not consent unless they can pay the bride price.’ Let them be paid so that the Aramaeans can get married. (Source)

Of course, destroying these peoples’ entire worlds and resettling them where they were to serve their conqueror’s needs does not a brownie point make, but considering the way war usually ended for the defeated in antiquity, well, it’s a little less horrible to be resettled and given a job and, apparently, a life partner.

Say it in Aramaic

Though Assyria had absorbed many different peoples through its expansion, there was one particular group Assyrians had done that a lot with: speakers of Aramaic.

Aramaic was a language spoken by those hailing from Aram, a group of city-states in what is modern-day Syria. They were a people Assyria had been picking fights with since the reign of the first Tiglath-Pileser in the 11th Century BCE. TPIII had resettled and assimilated so many Aramaeans as he expanded his empire, it was virtually overrun with them.

Perhaps to make things easier, what with so many people speaking it already, or perhaps because of the ease of Aramaic compared to Assyria’s Akkadian, TPIII eventually made Mesopotamian Eastern Aramaic the official language of the Assyrian Empire. One can only deduce that when the Romans made Latin their lingua franca centuries later, it was TPIII’s example they were following.

He Did it His Way

Tiglath-Pileser III’s reign lasted 17 years, filled with war, conquest, innovation and invention. He had even managed in that time to crown himself king of Babylonia in 729 BCE when a revolt broke out there after the death of its Assyrian ally king Nabonassar (747 – 734 BCE).

Pretty much everything TPIII did was carried out in the same spirit as the one in the opening image of this post–a reinforcement of Assyria’s dominance and hold on the region. By the time he died in 727 BCE from natural causes, TPIII had built an invincible empire that would continue to flourish with a line of equally consequential and notable kings, including his son Sargon II (722 – 705 BCE) and the last of the great kings of Assyria, his great-great grandson Ashurbanipal (668 – 627 BCE).

Mark sums up the legacy of the third Tiglath-Pileser best in his Tiglath-Pileser III article, and perhaps helps scholars’ argument along that the Neo-Assyrian era began with this mysterious yet determined man:

“Tiglath Pileser III’s achievements laid the foundation for the future of the Assyrian Empire, which has come to be recognized as the greatest political and military entity of its time and the model on which future empires would be based.” (Source)