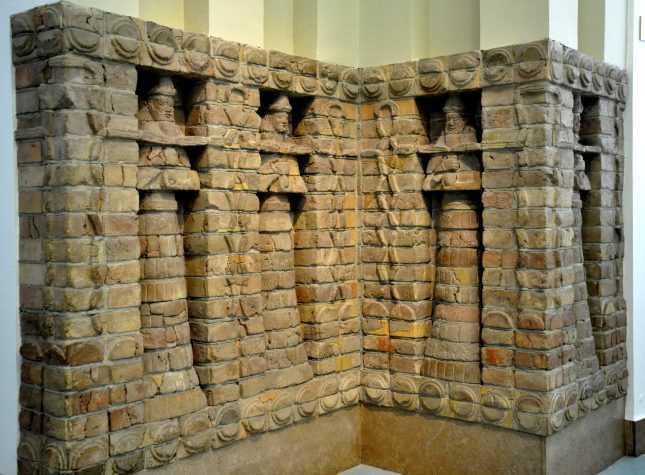

E-anna, Inanna’s residence at Uruk. (Source)

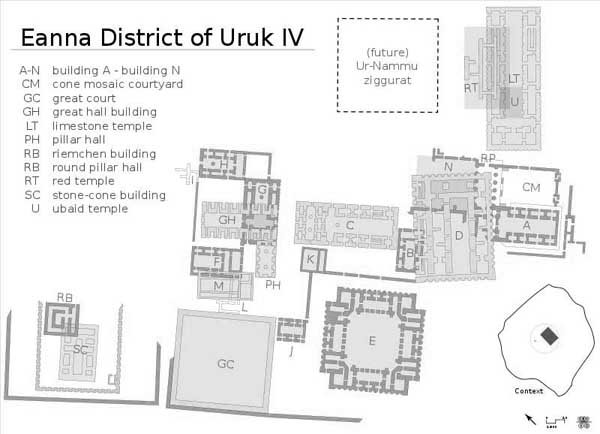

When the city of Uruk was first excavated in the mid-nineteenth century, it was found to be split in half, with one section walled off. That division of the ancient city now known as Warka in modern-day Iraq, once considered the most important in ancient Mesopotamia, represented a marker between two districts: the Anu and the Eanna.

The Anu District was the older section of the two, and dedicated to the sky-god An (Anu). The Eanna District–the walled off one–was dedicated to Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and eventually, war.

No one knows exactly why the Eanna District was walled off, especially when one temple, the E-anna (Sumerian for “House of Heaven”), figuratively housed both Inanna and An.

Map of the Eanna District, which was “composed of several buildings

with spaces for workshops, and was walled off from the city.” (Source)

Some, like Joshua J. Mark in his “Uruk” entry at Ancient History Encyclopedia, look at Inanna herself for a possible answer:

“…since Inanna is regularly depicted as a goddess who very much preferred things her own way, perhaps the walled district was simply to provide her with some privacy.” (Source)

Uruk was the birthplace of writing, stonework in architecture and the cylinder seal. It was also the birthplace of something hardly ever considered or discussed when looking at ancient firsts; “Uruk could also be credited as the city which first recognized the importance of the individual in the collective community,” Mark writes. (Source)

If Mark is correct, and the Eanna district was walled off simply to give Inanna her own space and privacy, then the birth of individualism under her watch is another piece of the puzzle that is this goddess, whose trials and tribulations to assert her dominance and power over everything, from gods to men, and even mountains, were the subject of many a myth and hymn.

Who’s that goddess?

“Akkadian cylinder seal dating to c. 2300 BC depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, and Enki…” (Source)

With the eventual title of “Queen of Heaven and Earth,” (and you’ll see why I say eventual again, eventually) Inanna appears in the earliest god lists; she has been there since the beginning, as far back as 4000 BC, and pretty much set up the game for the Greek Aphrodite and Athena, as well as the Roman Venus.

Born in the Mesopotamian heavens, and, depending on the era in which a myth was told of which she was often a subject, Inanna’s genealogy is confusingly varied. She is sometimes presented as the daughter of An (Anu), the supreme sky god. Other times she is presented as the daughter of the water god Enki. Even the air god Enlil is presented as her father. And we’re not even done yet, because the renowned Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer traces Inanna’s parentage to the moon god Nanna and his consort Ningal in his book, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer.

As for siblings, Inanna has a few. Kramer writes that Inanna is the sister of the sun god Utu (various other sources assert that they are twins, even), and through her myths we know that she is also the sister of the goddess of the underworld Ereshkigal, as well as the sister of the god of storms Adad.

Sex, agriculture and reed…

Inanna started out and remained a goddess of agriculture. Because of this, her symbol and cuneiform ideogram were a knot of reeds, appropriately called Inanna’s Knot.

Inanna’s Knot. It “represents a door-post made from a bundle of reeds, the upper ends, bent into a loop to hold a cross-pole.” (Source)

The knot of reeds was a symbol of Inanna’s role as a fertility goddess, fertility being a stand-alone concept applicable to any area in which abundance is desired, mostly but not limited to the context of agriculture.

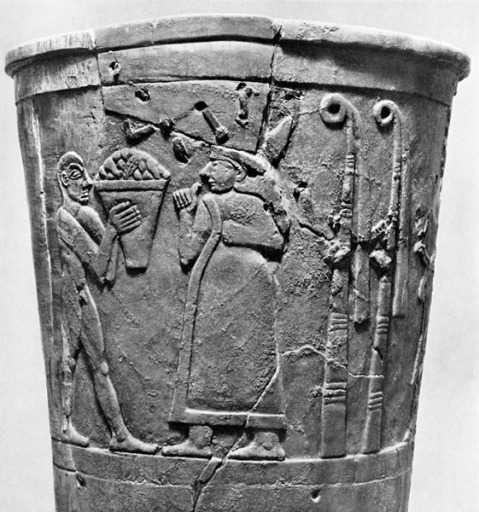

It is believed the woman pictured on the top register of the Warka (Uruk) Vase, at the National Iraqi Museum, is Inanna. Aside from the vase being found at her temple at Uruk, the two reed bundles behind her are indicators of the female figure being Inanna. (Photo: Hirmer Verlag, Source)

The flexibility of Inanna’s fertility aspect extends to the Sacred Marriage, an annual event in which a high priestess and the king (or high priest if the king isn’t up to it) would perform a marriage and consummation ceremony between Inanna and Dumuzi. Also known as Dumuzid, Dumuzi was a god of fertility. This symbolic union was enacted to bring fertility to the land each spring, ensuring a new year of abundance in crops and herds, and on a less ostentatious scale, for human offspring as well.

As Inanna expanded her domain, so did she acquire more symbols, including the eight-pointed star, aka planet Venus, and the eight-pointed flowery rosette. I like the way Chandra Alexandre describes these two eight-centric symbols in her post titled, “The Eight-Pointed Rosette Star of Inanna,” as “…images that capture both the intensity of a star and the subtle delicacies of a flower,” which “reflect well the Goddess’ paradoxical nature.”

Inanna was known as the Morning and Evening Star. The eight-pointed star of Ishtar (Inanna), aka planet Venus. The eight points represent “the movements of the planet,” aka the morning star, and it is why the city of Babylon had eight gates. (Source)

Lapis lazuli was imported into ancient Mesopotamia from Afghanistan, and was prized more than any other precious stone. (Source)

Lions were also a symbol associated with Inanna in relation to her war aspect. Other associations include lapis lazuli, as Inanna wore a necklace made of the precious stone that identified her as a harlot in one myth. Because Inanna represents both feminine and masculine aspects as a goddess of love and war, it is believed that the colors associated with her, “red and carnelian, and the cooler blue and lapis lazuli,” are meant to highlight those aspects.

Love is a battlefield…

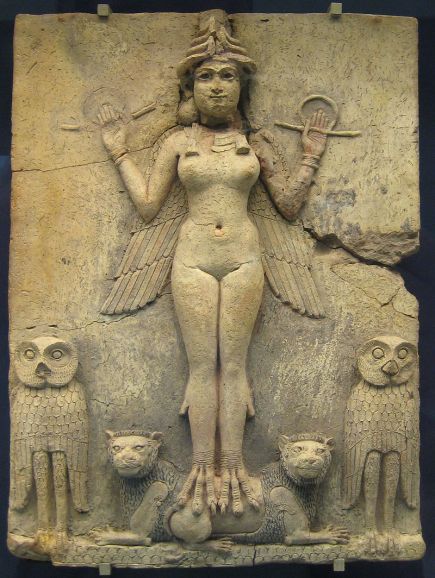

Google “Inanna” or “Ishtar” and this image of the Burney Relief, aka “Queen of the Night,” will pop up. The thing is, it’s in dispute which deity is actually pictured here. The wings, nudity, horned headdress and lions under the figure’s feet make for a strong argument that the “Queen of the Night” is a depiction of Inanna/Ishtar. Further, the bottom of the relief depicts a mountaintop, which is another indicator it might be Inanna, as her home is on a mountaintop “to the east of Mesopotamia.” (Source)

The Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses entry for Inana/Ištar begins with a very fitting introduction to the goddess that emphasizes further Inanna’s paradoxical nature:

“Inana/Ištar is by far the most complex of all Mesopotamian deities, displaying contradictory, even paradoxical traits.” (Source)

With appearances peppered throughout ancient Mesopotamian literature and myth, including in the Epic of Gilgamesh, we really get a feel for the above-mentioned complexity and how it is manifested.

Let’s go back to the Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses entry and zoom in on what those “paradoxical traits” actually are, complete with links:

“In Sumerian poetry, [Inanna] is sometimes portrayed as a coy young girl under patriarchal authority (though at other times as an ambitious goddess seeking to expand her influence, e.g., in the partly fragmentary myth Inana and Enki, and in the myth Inana’s Descent to the Nether World). Her marriage to Dumuzi is arranged without her knowledge, either by her parents or by her brother Utu. Even when given independent agency, she is mindful of boundaries: rather than lying to her mother and sleeping with Dumuzi, she convinces him to propose to her in the proper fashion. These actions are in stark contrast with the portrayal of Inana/Ištar as a femme fatale in the Epic of Gilgameš.” (Source)

I think it helps one work through this paradox to think of Inanna’s love aspect as an umbrella term that covers all the other stuff she is known for, like sex, passion, sensuality, and prostitution, all of which are ultimately tied to fertility as that stand-alone concept I talked about.

Further, this treatment of the concept of fertility helps to explain why Inanna, who would become the Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian Ishtar, was never portrayed as a mother goddess. Dr. Jeremy Black explains this combo best while erasing the mother goddess image that usually comes to mind when we talk about a fertility goddess:

“One aspect of [Inanna’s personality] is that of a goddess of love and sexual behaviour, but especially connected with extra-marital sex and – in a way which has not been fully researched – with prostitution.” (Source)

So, Inanna’s sensuality and sexuality are pretty prominent and very much entwined with her agricultural side–that connection is never broken and is almost always alluded to. Oftentimes, even, Inanna’s sexuality is a vehicle for that ever-present connection to be manifested.

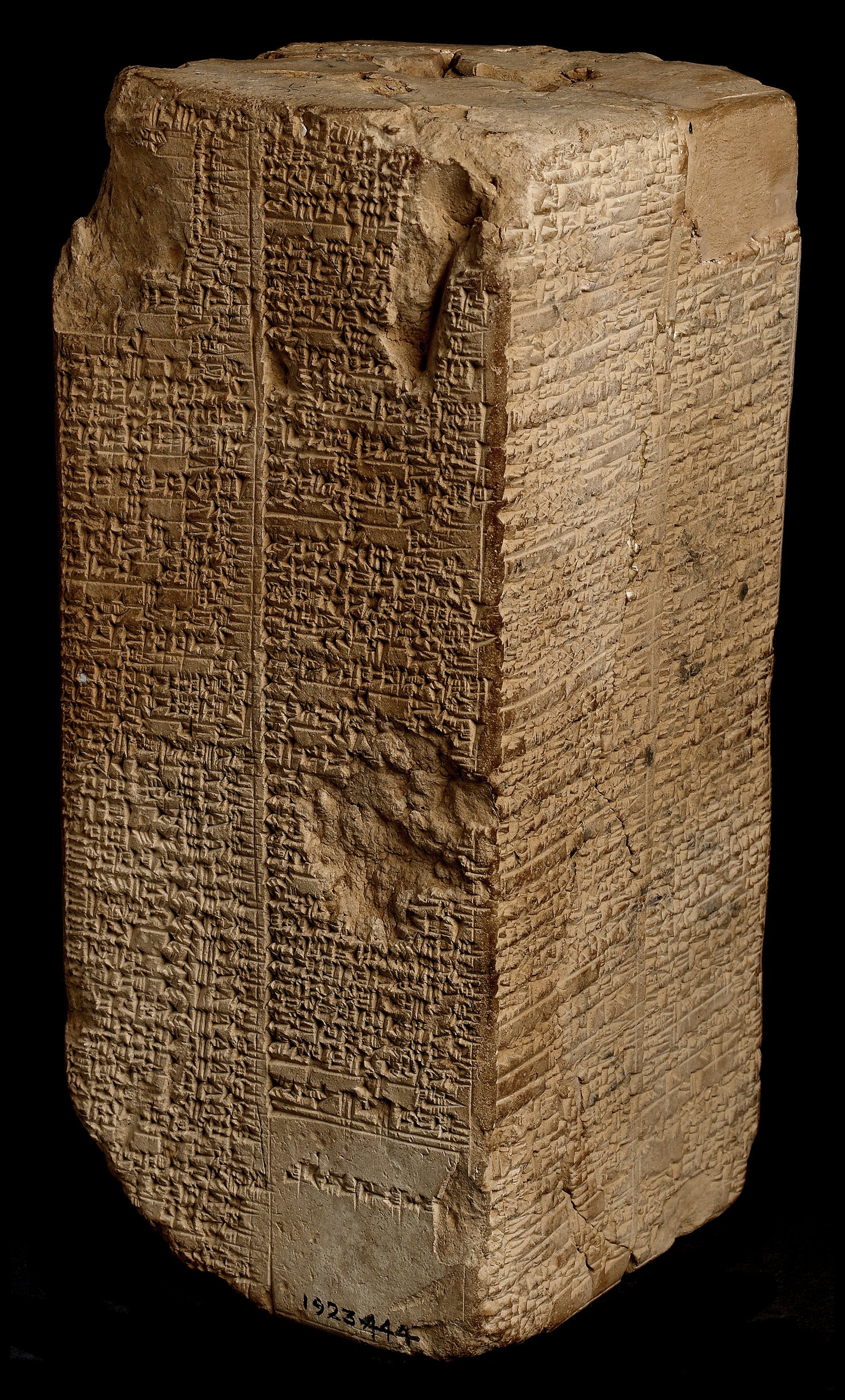

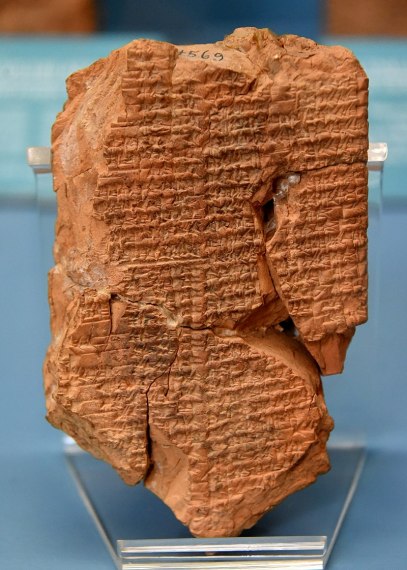

‘Original Sumerian tablet of the Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzid. “Inanna prefers the farmer” terracotta tablet. Here, in this myth, Enkimdu (god of farming) and Dumuzi (god of food and vegetation) tried to win the hand of the Sumerian goddess Inanna. Sumerian language. From Nippur (modern Nuffar, Al-Qadisiyah Governorate, Iraq). 1st half of the 2nd millennium BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul’ (Source)

For example, in the myth of The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi, there is a romantic exchange in which Inanna playfully asks Dumuzi: “Who will plow my vulva?” (Dumuzi says he will, in case you’re worried.)

We’re talking about sex and sensuality here, but the agricultural reference couldn’t be any clearer, right?

Now take for another example the myth of Inanna and the God of Wisdom; our subject is about to go on a, uh, non-sexual mission, one that will alter the Mesopotamian way of life altogether forever. After she puts on her crown and heads out, she stands under an apple tree, and, as Dr. Honora M. Finkelstein notes, ‘”she displays and exults in her “wondrous vulva.”‘

Finkelstein explains the reason for the seemingly out-of-the-blue reference to female genitalia here:

“This description, so straightforward in terms of showing her female power, demonstrates immediately that Inanna has moved into a new phase of her development—she is showing herself as ready to be both queen and sexual woman. Also, in ancient cultures, the vulva was seen as the source of all life; the world itself was sometimes pictured as having emerged from the female birthing canal. And the vulva, as vessel, was sometimes viewed as a container, a boat, an ark, etc.” (Source)

And Inanna’s vulva makes appearances all over the place, including in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where Inanna’s sexuality and passion are on full display. In that story, she seduces and propositions the eponymous hero to be her lover, like so: “…stretch out your hand to me, and touch our vulva.”

Quite the far cry from someone whose marriage is arranged without her knowledge, huh? But here’s the thing: though this goddess is, shall we say, generally mercurial, there is a big picture to be seen through her myths, a cycle that explains how in one instance she’s having a marriage arranged without her knowledge and in the next asking a man to touch her vulva.

This idea of a cycle is introduced by Diane Wolkstein in her introduction to Samuel Noah Kramer’s book, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer:

‘Here, then, is the Cycle of Inanna. In ‘The Huluppu-Tree;’ she [is presented] to us as a young woman in search of her womanhood. In “Inanna and the God of Wisdom,” she achieves her queenship. In “The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi,” she chooses the shepherd Dumuzi to be her lover, her husband, and the King of Sumer. In “The Descent of Inanna,” Inanna leaves for the under- world and is allowed to return from the Great Below only on the condition that she choose a substitute. In the last section of the cycle, the “Seven Hymns to Inanna,” Inanna is greeted and loved in her many aspects…

…the texts formed one story: the life story of the goddess, from her adolescence to her completed womanhood and “godship.”‘ (Source)

Inanna is a character, a heroine in a series, sometimes even an anti-heroine, fleshed out and having a literary arc.

What’s love got to do with it?

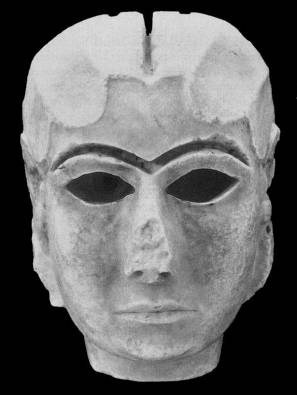

It is believed the Lady of Uruk (or Mask of Warka) might depict Inanna’s face. If so, that’s quite the death stare, and one Gilgamesh and Dumuzi might have gotten before horrible things befell them. (Source)

So, we’ve established Inanna is a hypersexual being, to say the least, but we also need to put it out there that she was quite passionate for better and worse.

When her amorous proposition to Gilgamesh is rejected with not just a simple no but also a list of her past lovers and how she wronged each one, Inanna’s passion comes into play for the worse. I mean, that rejection enrages her to the point where she lashes out so hard, she causes the death of her brother-in-law, the Bull of Heaven, which eventually also leads to the death of Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s companion. Conversely, in her exchange with Dumuzi, we see love and passion with a dousing of sensuality: better (as long as we ignore Dumuzi’s fate at Inanna’s hand in a later myth, anyway).

The Gilgamesh example supports Mark’s description of at least part of Inanna’s persona (and will come full circle in a bit):

“…a brash, independent young woman; impulsive and yet calculating, kind and careless with others’ feelings or property or even their lives.” (Source)

Now just as important as what Inanna is, is what she is not.

We’ve established she’s not a mother goddess, but also, even as the bride in the Sacred Marriage, and even as a wife to Dumuzi, Inanna is never the model of a wife and neither is her marriage exemplary. In fact, Inanna’s description in The Mesopotamian Pantheon entry at Ancient History Encyclopedia states that she is often depicted as unmarried.

Mark quotes Dr. Black further on this subject in his Inanna entry:

“Inanna is not a goddess of marriage… The so-called Sacred Marriage in which she participates carries no overtones of moral implication for human marriages.” (Source)

Dr. Black goes on:

“Inanna is always depicted as a young woman, never as mother or faithful wife, who is fully aware of her feminine power and confronts life boldly without fear of how she will be perceived by others, especially by men.” (Source)

Through numerous Sumerian texts we see what Dr. Black means when he also describes Inanna as, “violent and lusting after power.” Two myths in particular, Inanna and the God of Wisdom and Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld, demonstrate Inanna’s hunger for power in every area of her existence, and how far she’s willing to go to obtain it, regardless of what or whom is standing in her way.

In Inanna and the God of Wisdom, our subject sets her sights on the Me, a set of divine decrees that Kramer describes as the “basis of the culture pattern of Sumerian civilization.”

To possess the Me is to possess power, so Inanna sets out from Uruk to Eridu, the home of Enki (the god of wisdom who is sometimes presented as her father, remember), who happens to be the guardian of the Me. After a lavish dinner and some drinking with his guest, a drunk Enki all but hands over the decrees to Inanna who absconds with them back to Uruk. Through this act she has essentially unseated Enki as the god of the most important city in Mesopotamia, thereby raising her status in the Mesopotamian pantheon while simultaneously replacing Eridu with Uruk as the most prominent city in all of Sumer. The myth is symbolic of the shift from one way of life to another in Mesopotamian culture; Mark writes in his Uruk entry at Ancient History Encyclopedia that Uruk was “the embodiment of the new way of life – the city,”; Eridu represented the old, rural way of life.

Alongside this myth explaining Uruk’s rise as the work of the gods, it also showcases Inanna’s hunger for power, this time for the good of the whole. Further, it showcases her manipulative side.

Next, Inanna’s Descent to the Nether World, told in poem form, begins with the following:

“From the great heaven she set her mind on the great below. My mistress abandoned heaven, abandoned earth, and descended to the underworld. Inana [sic] abandoned heaven, abandoned earth, and descended to the underworld.” (Source)

In this myth, the goddess is not satisfied with just heaven and earth as her realms of power, so she sets her sights on her older sister Ereshkigal’s domain. Inanna descends to the underworld under the pretense of a sister attending the funeral of her brother-in-law and is met with a lot less hospitality than she was at Eridu. She is, after all, responsible for her brother-in-law’s death at this point, for it was her rage at Gilgamesh’s rejection that led to her summoning the Bull of Heaven, Ereshkigal’s husband.

Ereshkigal is understandably angry with her sister. She kills Inanna and keeps her in the underworld, from whence no one ever returns. And this is awkward, because it is with the help of Enki, the one from whom Inanna stole the Me, that she is able to go back to the land of the living, but only if someone takes her place in the underworld…them’s the rules, as they say.

Driving further the idea that her marriage is far from exemplary (and really making the title of this section come to life), Inanna chooses Dumuzi, her husband (I told you his accepting Inanna’s invitation to plow her vulva would not end well), to replace her in the underworld after finding he is not too torn up about her death.

This myth is telling of just how little thought Inanna gives to how her actions affect others; she attends her brother-in-law’s funeral for whose death she is responsible in an attempt to extend her domain by taking over her sister’s–a widow in mourning–only to use her husband as her replacement in the underworld.

And here you thought your sister was the worst for stealing your favorite sweater!

Roxanne…

Inanna, goddess of sex. (Source)

Prostitution in ancient Mesopotamia is misunderstood by our modern standards. It’s okay, though, because even the ancient Greeks couldn’t wrap their minds around prostitution in ancient Mesopotamia. In the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484-425/413 BC) famously visited Babylon and recorded a prostitution practice that pretty much forever tainted the image of the city as a place of excess, and loose morals and women.

Before I go any further, let me say that although there is one other source (Strabo, a Roman whose writings are some 500 years after Herodotus) that backs up this particular Herodotus description, as a general rule it seems scholars either include a disclaimer that he is not a reliable source, or they ignore him altogether. Consider this a disclaimer in which I ask you to take what Herodotus witnessed with the proverbial grain of salt…

Now, it’s important to note that the oldest profession in the world, as we know it to this day, did exist in ancient Mesopotamia – it existed alongside a “sacred version,” known as “Sacred Prostitution.” It is described in this entry at History on the Net as “a religious act of devotion to the goddess rather than as sex per se.”

Herodotus being all misinterpret-y. (Source)

Let’s now look at what Herodotus wrote:

“Every woman born in the country must once in her life go and sit down in the precinct of Venus [Mylitta], and there consort with a stranger…. A woman who has once taken her seat is not allowed to return home till one of the strangers throws a silver coin into her lap, and takes her with him beyond the holy ground…. The silver coin maybe of any size….

The woman goes with the first man who throws her money, and rejects no one. When she has gone with him, and so satisfied the goddess, she returns home, and from that time forth no gift however great will prevail with her.” (Source)

Sounds like a woman’s status is elevated rather than lost by the act Herodotus described here, therefore, it’s Sacred Prostitution he witnessed and not prostitution-prostitution.

The History on the Net article further explains this practice:

“Sacred prostitution involved temple priestesses of Inanna/Ishtar having ritual sex with male visitors to the temple, again releasing the divine fertile energy.” (Source)

Further, in an article from Ancient Origins titled “The Secret Life of an Ancient Concubine,” Joanna Gillan writes that men belonging to the elite ranks of some Mesopotamian societies, including Babylonia, took up concubines and visited them as prostitutes, helping them fulfill a religious duty. “…men would visit these women as prostitutes, which society not only condoned, but considered an honourable fulfilment of religious duty…,” writes Gillan, pointing out that these women were priestesses with high ranks in society of their own.

So, I don’t know about you, but it sounds to me like Herodotus maybe should’ve taken a chill pill.

QUEEN!

Throughout the land, men served alongside women at Inanna’s temples. They served her as priests, servants and sacred prostitutes. Mark writes in his Inanna entry that the reason both genders were employed at Inanna’s temples may have been “to ensure the fertility of the earth and the continued prosperity of the communities.”

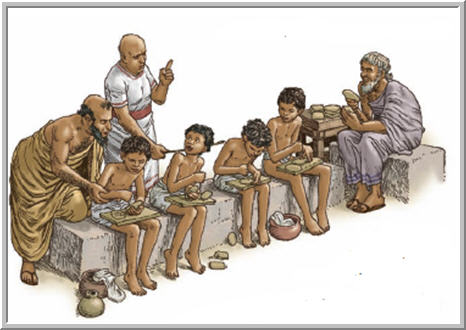

A couple of Gala priests, employees of the temple of Inanna. (Source)

This seems a good point at which to talk about the priests involved in the cult of Inanna/Ishtar, known as gala priests. Gala priests sang lamentations and had homosexual intercourse. In an article titled “Evidence for Trans Lives in Sumer” at NOTCHES, Cheryl Morgan explains that, “A gala is a temple employee whose job it is to sing lamentations…They appear to have spoken a Sumerian dialect called Emesal which was possibly reserved for women.”

But wait, there’s more. In an article at Hornet, titled, “How a Sumerian Goddess Turned Gender on Its Head,” R.S. Benedict writes about the most progressive aspect of Inanna; that based on fragmentary texts, the cult of Inanna performed a ritual involving a gender transformation ceremony. Benedict writes, “…it looks pretty clear that the goddess Inanna oversaw a ceremony referred to as the head-overturning, by which a man was transformed into a woman, and a woman transformed into a man.”

Keep in mind that all of what we’ve discussed so far is the feminine side of Inanna, a goddess often labeled androgynous, though not without controversy, and I recommend you give Cheryl Morgan’s article a read, as she thoroughly puts into perspective how complicated the subject of gender and gender transformation around Inanna and in ancient Mesopotamia truly are, and in how many ways the information we have can be interpreted and misinterpreted.

Nonetheless, let’s now talk about Inanna’s masculine aspect…

She is the warrior…

In his book, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, Samuel Noah Kramer writes about a movement in the third millennium BC that helped fuse an established Sumerian pantheon with an Akkadian one:

“During the third millennium B.C., there were periodic attempts to unify the various city-states in Sumer and Akkad; and with the increasing political centralization came a concurrent movement to bring together the many local gods and goddesses into one pantheon.” (Source)

With the help of his daughter Enheduanna (2285-2250 BC) (who would become the world’s first-named author and high priestess of the temple of Inanna at Ur and Uruk), Sargon of Akkad (c. 2234-2279) was able to create such a pantheon. Through her poetry, Enheduanna reinforced Inanna’s image as the feminine goddess that she already was, and gave her her masculine side.

Enheduanna, high priestess of Inanna and world’s first-named author. (Source)

Joshua J. Mark writes in his Enheduanna entry that the poetess basically took “a local Sumerian deity associated with fertility and vegetation,” and merged her with the “much more violent, volatile and universal Akkadian goddess Ishtar, the Queen of Heaven.”

So it was through Enheduanna’s writings that Inanna acquired her masculine war aspect, the title, “Queen of Heaven,” and the name Ishtar. As a result of these additions, cults dedicated to Inanna grew in popularity, and she herself grew in importance within the new Sumero-Akkadian pantheon.

And the war thing really stuck; one cited source I found mentions that battle itself came to often be known as the “Dance of Inanna.”‘

“Ancient Akkadian cylinder seal depicting Inanna resting her foot on the back of a lion while Ninshubur stands in front of her paying obeisance, c. 2334-2154 BC.” (Source)

Through Enheduanna’s poem Inanna and Ebih, in which the frustrated goddess destroys a mountain against the advice of An, we get our first description of Inanna as an all-out warrior, complete with a shield and weapon:

“Goddess of the fearsome divine powers, clad in terror, riding on the great divine powers, Inana, made complete by the strength of the holy ankar weapon, drenched in blood, rushing around in great battles, with shield resting on the ground (?), covered in storm and flood, great lady Inana, knowing well how to plan conflicts, you destroy mighty lands with arrow and strength and overpower lands.” (Source)

Though she continued to be depicted naked when representing her feminine persona as an agricultural goddess of love and fertility, Inanna donned a suit of armor to represent her masculine aspect of war (see above). To complete the ensemble, she carried a weapon in one hand, and a bow and quiver of arrows slung across her shoulder that pointed out from behind her like rays (of death!). She rode into battle standing atop lions, sometimes sporting a beard to emphasize this masculine side.

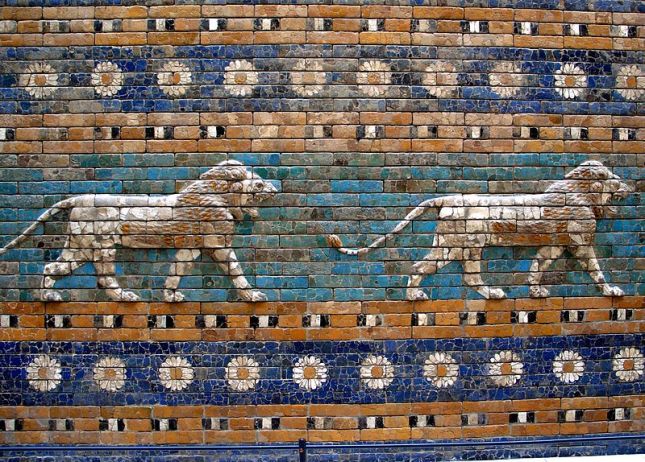

- North of the famous Ishtar gate was the processional way, which was decorated with striding lions, and eight-pointed flower rosettes, both symbols of the goddess of love and war, representing both her masculine and feminine aspects, respectively. (Source)

Invoked by kings on the battlefield and off, the new goddess of war became their protector. Writing that Sargon of Akkad claimed Inanna as his “divine protector,” Mark also points to Gwendolyn Leick’s writing on how Inanna helped a king on and off the battlefield: “Sargon of Akkad claimed her support in battle and politics.”

Later, Sargon of Akkad’s grandson Naram-Sin (c. 2254-2218 BC) would also follow suit and invoke her in his inscriptions, referring to her as the “warlike Ištar.” (Source)

I can’t help but credit this important function as protector and advisor to kings as at least half the reason for Inanna’s survival beyond the shift away from goddess worship in Mesopotamian religion.

Girl from Uruk goes to Babylon…

“A hand of the Goddess Ishtar (Inanna). This is a decorative element of architecture which was used in temples and palaces. It is inscribed with cuneiform inscriptions and was found in the palace of Ashurnasirpal II to commemorate the new foundation of God Ninurta‘s temple at Nimrud, the Assyrian capital. Reign of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Sulaimaniya Museum, Iraq.” Credit: Osama Shukir Mohammed Amin (Source)

I came across an article recently that delved into the evolution of religion throughout human history. In the article, published in York University’s community newspaper, Dylan Stoll acknowledges the role cuneiform played in helping us piece together the workings of ancient religion. “…cuneiform,” he writes, “…inadvertently permitted modern man to view the ancient world of the Sumerian people through a lens less muddied by the conjecture associated with a lack of written proof.”

To continue with that line of thought that Stoll introduced, cuneiform also showed us the shift in ancient Mesopotamian religion away from Sumerian goddess worship in the 2nd millennium BC.

Mark, in his Inanna entry, clarifies for us how truly ahead of their time Sumerians were when it came to women: “In Sumerian culture women were regarded as equals and even a cursory survey of their pantheon shows a number of significant female deities…” But this didn’t last long, unfortunately, as women lost their status in Mesopotamian society, particularly under the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC), as did goddesses in the Mesopotamian pantheon.

But not Inanna/Ishtar.

“The fact that the Sumerians could conceive of such a goddess [as Inanna] speaks to their cultural value and understanding of femininity,” Mark writes. And it is precisely that very representation of femininity that I believe is the other half of what saved Inanna from a fate of obscurity. As Hammurabi minimized and eliminated goddesses to replace them with male deities, there was still a need for a representation of femininity and womanhood. It seems no amount of patriarchy can erase the importance of femininity and its power.

She is every woman…

Just a bunch of Inannas. (Source)

Inanna survived long, far and wide, and went on to become the most recognizable and accessible goddess in the whole of the Mesopotamian pantheon, worshiped and served by both women and men. To this day, women looking to tap into their inner goddess turn to Inanna, marveling at her embodiment of womanhood, and taking cues from her in how to be unapologetically a determined woman, or just simply yourself, regardless of your gender. Never apologize for being yourself, she seems to be telling us women and men alike.

“Inanna made people want to serve her because of who she was,” Mark writes.

And who was Inanna?

Why, every woman, of course.

Inanna. Ishtar. Every woman. (Source)

Sources & further reading:

Uruk, Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uruk#Eanna_district

Uruk, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/uruk/

Anu (An) https://www.ancient.eu/Anu/

Eanna, Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eanna

Map of Eanna District of Uruk, Sumerian Minor Gods and Goddesses http://www.crystalinks.com/sumergods1.html

Cylinder Seals in Ancient Mesopotamia – Their History and Significance https://www.ancient.eu/article/846/cylinder-seals-in-ancient-mesopotamia—their-hist/

Enki, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/Enki/

Enlil, Wikipedia https://www.ancient.eu/Enlil/

Nanna, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/Nanna/

Ningal, Gateways to Babylon http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/gods/ladies/ladyningal.html

Utu, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/Utu-Shamash/

Utu/Šamaš, Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses https://www.ancient.eu/Utu-Shamash/

Ereshkigal, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/Ereshkigal/

Adad, Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/listofdeities/ikur/

Knot of Inanna, Symbol Dictionary http://symboldictionary.net/?p=2991

Warka Vase, smarthistory.org https://smarthistory.org/warka-vase/

Sacred Marriage and Sacred Prostitution in Ancient Mesopotamia https://www.historyonthenet.com/sacred-marriage-and-sacred-prostitution-in-ancient-mesopotamia/

The Eight-Pointed Rosette Star of Inanna, Sharanya.org http://sharanya.org/mandala/the-eight-pointed-rosette-star-of-inanna/

Lapis lazuli, Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lapis_lazuli

Dumuzi/Tammuz, New World Encyclopedia http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Tammuz

Inana and Enki, ETCSL etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi

Epic of Gilgamesh, Classical Literature http://www.ancient-literature.com/other_gilgamesh.html

Epic of Gilgamesh, Archive.org https://archive.org/stream/TheEpicofGilgamesh_201606/eog_djvu.txt

Inanna and the God of Wisdom, Course Hero https://www.coursehero.com/file/27636871/Inanna-and-the-God-of-Wisdomdocx/

Inana/Ištar (goddess), Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/listofdeities/inanaitar/

Inana’s descent to the Nether World: translation, ETCSL http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm

Eridu, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/eridu/

Inana and Ebih: translation (“Goddess of the Fearsome Powers”), ETCSL http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr132.htm

The Secret Life of an Ancient Concubine, Ancient Origins https://www.ancient-origins.net/human-origins-religions/secret-life-ancient-concubine-001301?fbclid=IwAR3WMr6TQRhXxVUcZk02eyKfF7cF9dDi9yovKOJyhAPh5Xg3l2G47Q7fTBM

Herodotus and Strabo on Babylonian Temple Prostitution, The Real Samizdat https://therealsamizdat.com/2015/04/07/herodotus-and-strabo-on-babylonian-temple-prostitution/

How a Sumerian Goddess Turned Gender on Its Head, Hornet https://hornet.com/stories/how-a-sumerian-goddess-turned-gender-on-its-head/

Evidence for Trans Lives in Sumer, NOTCHES http://notchesblog.com/2017/05/02/evidence-for-trans-lives-in-sumer/

The evolution and development of religion, Excalibur shttps://excal.on.ca/the-evolution-of-religion/?fbclid=IwAR2o2q1b2XO5secQUYrxDgzO63el-nUhfJwhh8z4PdjNn9MMRzJTUBcpImU

Hammurabi, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/hammurabi/

Naram-Sin, Ancient History Encyclopedia https://www.ancient.eu/Naram-Sin/